I'm currently reading a book by Peter Laufer called 'Forbidden Animals', about the trade in exotic pets. It's an absolutely fascinating book so far, but one thing I do notice is that the author and several of the subjects he interviews is that they're not particularly fond of zoos. Opinions have ranged from "I hate zoos" to "zoos are nothing but misery for animals", and that's only by page 65. I doubt I'll get many complimentary statements on the subject by the end of the book.

This is far from the only time I've read uncomplimentary statements about zoos. They used to upset me, but I've come to understand that my experience of zoos is very different from that of the people like Laufer and the people he talked to. I've been very lucky in that my zoo memories come from a much happier place, both for myself and for the animals, and I do want to talk about it for a bit because I fully believe that there is a difference between being opposed to zoos in principle and being opposed to the way many zoos operate in practice.

To start, it's worth understanding that the Minnesota Zoo opened when I was three years old, less than ten miles away from my house. My parents bought a zoo membership every year for most of my childhood, which meant that admission was free, and as such they were perfectly happy to take my sisters and I to visit on a weekly basis. The exhibits have changed slightly over the years--I'm still slightly surprised at times to find komodo dragons and DeBrazza's monkeys where I vividly remember caimans and sloth bears--but I am familiar with every inch of that zoo.

This is important, because as a child I also happened to be a big fan of the books written by naturalist Gerald Durrell. Durrell was famous for his vivid, colorful accounts of the trips he took collecting animals for zoos, but he was even more famous for his decision to stop collecting animals for other zoos, which he thought were run badly and took little account of the welfare of the animals, and to start running his own zoo founded on his philosophy of what the role of a zoo should be in society.

For those of you not interested in chasing down all those links, I'll sum up. Durrell believed that the primary purpose of a zoo was to act as a habitat for animals that were endangered--a reservoir for the species in the event of extinction in the wild. He believed that it was the job of a zoo to make sure that these animals survived until they could be reintroduced to the wild as a species, and that displaying them to the public was primarily important to educate people on the role they could play in conserving nature. Keeping an animal purely for entertainment purposes was highly discouraged in his philosophy.

This filtered down to his philosophy on exhibit design. His priority, first and foremost, was the comfort of the animal. Viewing comfort of visitors wasn't even second on the list (that was ease of use for keepers). Exhibits should be as large or as small as needed to match the animals' preferred territory, and they should have areas to go if needed to get away from people. He was a pioneer in feeding animals the food that they preferred in nature, and in designing "enrichment"--activities that mimicked their natural behavior and kept them interested and engaged in daily life. (This is very different, by the way, from "animal shows". In a zoo designed according to Durrell's philosophy, animals are not asked to perform in any way, shape or form.)

The Minnesota Zoo, as long as I can remember, has been designed around those same philosophies. It is so close to Durrell's idea of a zoo that many of the exhibits are identical to the wildlife park he founded. When I go there, even today, I see happy, fulfilled animals that are not just surviving but thriving thanks to the hard work of dedicated people who put the animals' welfare first and foremost. I've been very lucky to have that as my amazing zoo all my life, and I sometimes forget that not everyone has had those experiences.

So for those of you who don't like zoos, I do understand. I hope that you follow those links and read about zoos that do treat the animals well, and I hope that we all someday reach a point where Durrell's philosophy has prevailed in the zoological world. Because a well-run zoo is really an animal's best friend.

Monday, June 29, 2015

Friday, June 26, 2015

Review: The Severed Streets

I started 'The Severed Streets', Paul Cornell's latest novel about a team of detectives who gain the second sight and can see all the magical secrets of London, right after finishing 'Ancillary Justice'. I'm already done with it. That should tell you something right there, but I will elaborate.

This is a gorgeous book. I've been following Paul Cornell's writing since the 1990s, when he was an up-and-coming young writer doing TV tie-ins for Doctor Who and teaching a generation of fans and professionals alike that "TV tie-in" doesn't have to mean "generic pastiche" (his Who novels are mostly out-of-print, but they've been adapted for audio by Big Finish and are worth a listen). His skill has always been in evoking powerful, deep emotions by forcing his characters to make meaningful choices with big risks. Oh, and for those of you who've seen 'Father's Day', his first televised Doctor Who story, you already know that his big theme is about family.

So it should come as no surprise that 'The Severed Streets' continues on in this tradition. One of the threads from his previous novel in this series, 'London Falling', comes to the forefront here as Ross, a character who discovered that her father resides in Hell, now discovers a way to bring him out of it. But as you can imagine, bringing someone out of Hell and back to the world of the living is something that is not easy, and coveted by many people...including Costain, the undercover detective for the team who learned towards the end of the novel that Hell awaits him for his sins in life. The "Get Out of Hell Free" card, and the things that both Ross and Costain are prepared to do to get it, propel the novel forward with ferocious speed.

This book also provides the first real background on the secret London the characters have stumbled into, and it's clearly something that has enough material to provide plenty of books. We see that there is a long, ancient occult tradition in London...and we also see that some very wealthy and powerful people have learned of its existence and are trying to buy their way in. The characters see first-hand how much friction this is already causing, and there's a very real sense that this is something that has the potential to get much, much worse before it gets better. If it does. (Hey, remember the Smiling Man from 'London Falling' who was orchestrating everything behind the scenes to slowly turn London into a grinding, miserable hell on earth? Yeah, he's not gone.)

All of these threads seem disconnected from the main plot at first--there's an invisible Jack the Ripper impersonator out there who kills rich white men. But Cornell does a masterful job of weaving all the disparate threads together by the end of the book in ways you don't necessarily see coming, and along the way he really puts the screws to his characters in ways that ratchet up the tension with each scene. It's a relentless book, feeling at times like a series of brutal initiation rituals for the nascent practitioners of magic, and at other times like they're making all too human mistakes. He does not pull his punches--there are some bits so intense I was almost moved to tears--but none of the big moments feel unearned. Cornell really made this universe and the people who live in it feel real, and their struggles feel touching.

Oh, and there's a celebrity cameo on page 110 or so that has to be seen to be believed.

On the whole, if you've read 'London Falling', this is everything good about that book amped up a couple more notches. If you haven't read 'London Falling', what a coincidence--I recommended that too!

This is a gorgeous book. I've been following Paul Cornell's writing since the 1990s, when he was an up-and-coming young writer doing TV tie-ins for Doctor Who and teaching a generation of fans and professionals alike that "TV tie-in" doesn't have to mean "generic pastiche" (his Who novels are mostly out-of-print, but they've been adapted for audio by Big Finish and are worth a listen). His skill has always been in evoking powerful, deep emotions by forcing his characters to make meaningful choices with big risks. Oh, and for those of you who've seen 'Father's Day', his first televised Doctor Who story, you already know that his big theme is about family.

So it should come as no surprise that 'The Severed Streets' continues on in this tradition. One of the threads from his previous novel in this series, 'London Falling', comes to the forefront here as Ross, a character who discovered that her father resides in Hell, now discovers a way to bring him out of it. But as you can imagine, bringing someone out of Hell and back to the world of the living is something that is not easy, and coveted by many people...including Costain, the undercover detective for the team who learned towards the end of the novel that Hell awaits him for his sins in life. The "Get Out of Hell Free" card, and the things that both Ross and Costain are prepared to do to get it, propel the novel forward with ferocious speed.

This book also provides the first real background on the secret London the characters have stumbled into, and it's clearly something that has enough material to provide plenty of books. We see that there is a long, ancient occult tradition in London...and we also see that some very wealthy and powerful people have learned of its existence and are trying to buy their way in. The characters see first-hand how much friction this is already causing, and there's a very real sense that this is something that has the potential to get much, much worse before it gets better. If it does. (Hey, remember the Smiling Man from 'London Falling' who was orchestrating everything behind the scenes to slowly turn London into a grinding, miserable hell on earth? Yeah, he's not gone.)

All of these threads seem disconnected from the main plot at first--there's an invisible Jack the Ripper impersonator out there who kills rich white men. But Cornell does a masterful job of weaving all the disparate threads together by the end of the book in ways you don't necessarily see coming, and along the way he really puts the screws to his characters in ways that ratchet up the tension with each scene. It's a relentless book, feeling at times like a series of brutal initiation rituals for the nascent practitioners of magic, and at other times like they're making all too human mistakes. He does not pull his punches--there are some bits so intense I was almost moved to tears--but none of the big moments feel unearned. Cornell really made this universe and the people who live in it feel real, and their struggles feel touching.

Oh, and there's a celebrity cameo on page 110 or so that has to be seen to be believed.

On the whole, if you've read 'London Falling', this is everything good about that book amped up a couple more notches. If you haven't read 'London Falling', what a coincidence--I recommended that too!

Monday, June 22, 2015

Review: Ancillary Justice

I like Terry Pratchett a lot more than I like JRR Tolkien.

I know that's an odd way to start out a review of Ann Leckie's Hugo Award-winning hard science fiction novel 'Ancillary Justice', but hear me out. The reason I like Pratchett more than Tolkien is that I always felt like Pratchett started with a story, and did about as much worldbuilding as he had to in order to explain the bits that were important to the story. Whereas Tolkien, I felt, really had much more interest in the language, history, culture, geography, et cetera, of the world he created--the story was really just a means to show it all off.

Some people love that kind of immersion. They want a world so real they can imagine inhabiting it, and can return to it every time they read the novel. Me, I'm not so much into that. I like to read a good story, and see worldbuilding only as a means to the end of telling the story you want to tell. This isn't to say I can't appreciate the craft of worldbuilding--Tolkien is a great author and I'd be a fool to say otherwise. But I know which one of the two I read for pleasure.

I think that's why, despite appreciating 'Ancillary Justice', I didn't really enjoy it all that much. There is a plot, and it's actually a very clever one. But Leckie takes a lot of time in getting to it; she's got a lot to say about the Radch, the empire that controls vast segments of the galaxy, and she wants you to really get a handle on the reality of living in the empire they've created. Vast chunks of the novel are taken up explaining customs, linguistics (yes, including the bit the book is famous for, that the default gender is "she") and politics of the Radch, long before the plot ever kicks into gear.

(It should be noted here that it probably doesn't help that half the book is an extended series of flashbacks that alternate with the main action. I can, to some extent, understand exactly why Leckie did it; the opening sequences, of the main character traveling to a distant ice planet in search of the tools of revenge against the woman who killed her...well, most of her...it's a great hook, and it would be hard to abandon it. But it does mean that there are two interweaving plotlines that both take a long time to get going, rather than one plotline that climaxes at the mid-point of the novel and another at the end.)

Still, for all I complain that I'd prefer more plot and less worldbuilding, the worldbuilding we do get is choice. The Radch has some wonderful thematic echoes of late-period Roman Empire, but there's a lot going on under the surface that's more reminiscent of the British Empire towards the end of its heyday, when people were just beginning to wake up to the idea that "loot and pillage other countries to civilize them" was not exactly the moral high ground it was once seen as. There's a lot here to reward careful reading.

There's also an excellent sci-fi conceit; the Lord of the Radch, Anaander Mianaai, is actually an intelligence spread out over multiple bodies throughout Radch space, ruling directly through thousands of host bodies (much like the main character did at one point before her core intellect was destroyed). Leckie does a lot with this concept, and every development of it is both interesting and proceeds logically from the one before. By the end, when the plot finally gets to gallop, you're definitely left wanting more.

That may, I suppose, also be seen as a weakness; this book does a lot of worldbuilding to set up the next two books that presumably will shake up the systems established here. But as I say, it is excellently-done worldbuilding, so fans of that kind of SF/F are going to have a lot to like. Me, I wasn't quite so enamored of it, but I can certainly see what all the fuss was about.

I know that's an odd way to start out a review of Ann Leckie's Hugo Award-winning hard science fiction novel 'Ancillary Justice', but hear me out. The reason I like Pratchett more than Tolkien is that I always felt like Pratchett started with a story, and did about as much worldbuilding as he had to in order to explain the bits that were important to the story. Whereas Tolkien, I felt, really had much more interest in the language, history, culture, geography, et cetera, of the world he created--the story was really just a means to show it all off.

Some people love that kind of immersion. They want a world so real they can imagine inhabiting it, and can return to it every time they read the novel. Me, I'm not so much into that. I like to read a good story, and see worldbuilding only as a means to the end of telling the story you want to tell. This isn't to say I can't appreciate the craft of worldbuilding--Tolkien is a great author and I'd be a fool to say otherwise. But I know which one of the two I read for pleasure.

I think that's why, despite appreciating 'Ancillary Justice', I didn't really enjoy it all that much. There is a plot, and it's actually a very clever one. But Leckie takes a lot of time in getting to it; she's got a lot to say about the Radch, the empire that controls vast segments of the galaxy, and she wants you to really get a handle on the reality of living in the empire they've created. Vast chunks of the novel are taken up explaining customs, linguistics (yes, including the bit the book is famous for, that the default gender is "she") and politics of the Radch, long before the plot ever kicks into gear.

(It should be noted here that it probably doesn't help that half the book is an extended series of flashbacks that alternate with the main action. I can, to some extent, understand exactly why Leckie did it; the opening sequences, of the main character traveling to a distant ice planet in search of the tools of revenge against the woman who killed her...well, most of her...it's a great hook, and it would be hard to abandon it. But it does mean that there are two interweaving plotlines that both take a long time to get going, rather than one plotline that climaxes at the mid-point of the novel and another at the end.)

Still, for all I complain that I'd prefer more plot and less worldbuilding, the worldbuilding we do get is choice. The Radch has some wonderful thematic echoes of late-period Roman Empire, but there's a lot going on under the surface that's more reminiscent of the British Empire towards the end of its heyday, when people were just beginning to wake up to the idea that "loot and pillage other countries to civilize them" was not exactly the moral high ground it was once seen as. There's a lot here to reward careful reading.

There's also an excellent sci-fi conceit; the Lord of the Radch, Anaander Mianaai, is actually an intelligence spread out over multiple bodies throughout Radch space, ruling directly through thousands of host bodies (much like the main character did at one point before her core intellect was destroyed). Leckie does a lot with this concept, and every development of it is both interesting and proceeds logically from the one before. By the end, when the plot finally gets to gallop, you're definitely left wanting more.

That may, I suppose, also be seen as a weakness; this book does a lot of worldbuilding to set up the next two books that presumably will shake up the systems established here. But as I say, it is excellently-done worldbuilding, so fans of that kind of SF/F are going to have a lot to like. Me, I wasn't quite so enamored of it, but I can certainly see what all the fuss was about.

Friday, June 19, 2015

Some Horn-Tooting!

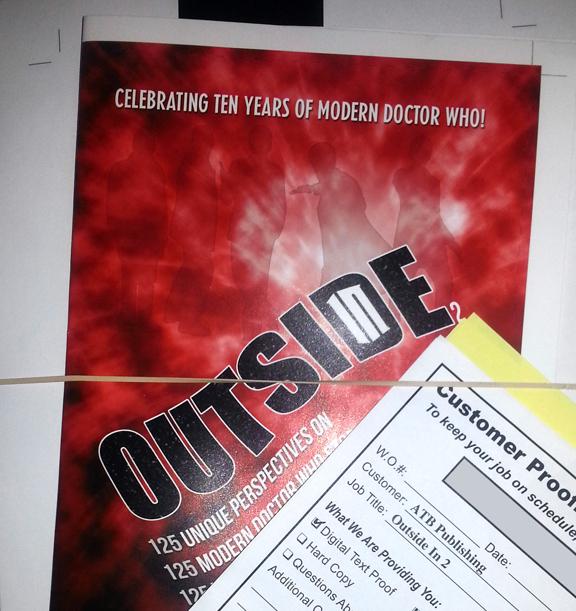

For those of you who enjoyed the original 'Outside In', which contained an essay on every story in the classic Doctor Who series by a different author for every story, the sequel is coming soon from ATB Publishing! This one will have, as you can see from the proof cover, 125 essays by 125 authors on 125 different episodes of 'Doctor Who'. I'm in there, writing about "The Christmas Invasion" and making what I think is a pretty credible case that it is not only meant to bookend "Rose", but also that it's meant to foreshadow the Tenth Doctor's descent into the Time Lord Victorious and eventual regeneration. I look forward to the book's arrival (once the madness of sorting out 125 author copies is past) and to talking about it at cons!

Labels:

books,

doctor who,

shameless plugs,

television,

writing

Tuesday, June 16, 2015

My Internet Points for the Day

A particularly sad Sad Puppy on File770 unironically stated the following:

It’s war, John; there aren’t any rules, only principles, and the only way to find even the approximate truth is by comparing the lies.

I read that statement. I actually read it a good two or three times, trying to imagine what kind of headspace it would have to have come from. I tried very hard to imagine being the kind of person--a veteran of military service, believe it or not--who could actually believe that war was waged through a series of increasingly outraged Internet blog posts, with a yearly smattering of casting ballots against the people who had committed the foul crime of being women and minorities. That this was not only a heroic action, but a significant and meaningful one. My response:

I want to frame this. Seriously, I want to frame it, light it up in neon, and take tours past it every half hour in perpetuity. “Yes,” the tour guide will say, “this is the smallest, pettiest, most unspeakably bitter and impotent statement ever uttered in support of an irrelevant, deranged and worthless cause. We have found it, and we have enshrined it here forever. Gaze upon it and know that whatever travails and trials and troubles might be present in your life, you have not been reduced to saying this on the Internet.”

I know, it's probably mean, but I want to keep it around if for no other reason than I think that sentence may provide people with comfort on bad days.

It’s war, John; there aren’t any rules, only principles, and the only way to find even the approximate truth is by comparing the lies.

I read that statement. I actually read it a good two or three times, trying to imagine what kind of headspace it would have to have come from. I tried very hard to imagine being the kind of person--a veteran of military service, believe it or not--who could actually believe that war was waged through a series of increasingly outraged Internet blog posts, with a yearly smattering of casting ballots against the people who had committed the foul crime of being women and minorities. That this was not only a heroic action, but a significant and meaningful one. My response:

I want to frame this. Seriously, I want to frame it, light it up in neon, and take tours past it every half hour in perpetuity. “Yes,” the tour guide will say, “this is the smallest, pettiest, most unspeakably bitter and impotent statement ever uttered in support of an irrelevant, deranged and worthless cause. We have found it, and we have enshrined it here forever. Gaze upon it and know that whatever travails and trials and troubles might be present in your life, you have not been reduced to saying this on the Internet.”

I know, it's probably mean, but I want to keep it around if for no other reason than I think that sentence may provide people with comfort on bad days.

Saturday, June 13, 2015

Additional Clarification to Previous Post

No, I did not intentionally arrange things so that the 'Megaforce' ad cut off where it did. As amusing as it wound up being, it was not a deliberate misrepresentation of the film to suggest that it featured Brad from Rocky Horror wearing a skin-tight jumpsuit and pointing out at the audience, saying, "Are You Man Enough For Me?"

But hey, if you want to do fanfiction about it, go for it.

But hey, if you want to do fanfiction about it, go for it.

Monday, June 08, 2015

Fame Is a Fickle Beast

The Onion AV Club has an interview with Barry Bostwick up today, part of their "Random Roles" series where they ask famous and well-respected actors about some of the more interesting parts in their long, distinguished careers. This is kind of weird for me, because my primary memory of Barry Bostwick is as the hero of the 1982 movie 'Megaforce'.

In fairness, I thought for years that it was Chuck Norris in 'Megaforce'. This is because my primary memory of 'Megaforce' is not the movie itself, but the ad for it that ran in dozens of comics when I was a kid:

There aren't any actors mentioned--it's just an ad for membership in a fan club for a movie that hadn't even come out yet, because it was the 80s and you could get away with stuff like that. The guy with the headband looked like Chuck Norris, so I assumed for years that it was a Chuck Norris movie and that it was some sort of cool live-action G.I. Joe pastiche full of awesomesplosions.

Then years later I saw it, and I realized that they must not have been able to get Chuck Norris and so they got Barry Bostwick instead and had him grow out a Chuck-style mullet and beard. Knowing what I know now about Bostwick's other parts, this has to be one of the most hilarious casting decisions in the history of cinema, but it's such a memorably goofy and terrible movie that it is my indelible association with the actor.

What I'd really like to know is if anyone else does this. Do any of my readers see Orson Welles and think, "Oh, right, Transformers!"? Or immediately jump to the conclusion that we're talking about 'Overdrawn at the Memory Bank' when we discuss Raoul Julia? Feel free to discuss your awkward actor associations in the comments!

In fairness, I thought for years that it was Chuck Norris in 'Megaforce'. This is because my primary memory of 'Megaforce' is not the movie itself, but the ad for it that ran in dozens of comics when I was a kid:

There aren't any actors mentioned--it's just an ad for membership in a fan club for a movie that hadn't even come out yet, because it was the 80s and you could get away with stuff like that. The guy with the headband looked like Chuck Norris, so I assumed for years that it was a Chuck Norris movie and that it was some sort of cool live-action G.I. Joe pastiche full of awesomesplosions.

Then years later I saw it, and I realized that they must not have been able to get Chuck Norris and so they got Barry Bostwick instead and had him grow out a Chuck-style mullet and beard. Knowing what I know now about Bostwick's other parts, this has to be one of the most hilarious casting decisions in the history of cinema, but it's such a memorably goofy and terrible movie that it is my indelible association with the actor.

What I'd really like to know is if anyone else does this. Do any of my readers see Orson Welles and think, "Oh, right, Transformers!"? Or immediately jump to the conclusion that we're talking about 'Overdrawn at the Memory Bank' when we discuss Raoul Julia? Feel free to discuss your awkward actor associations in the comments!

Monday, June 01, 2015

Awkward Question of the Day

I saw on the Gawker network that today was actually a holiday in Alabama honoring Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Now, this is the Internet, home of extraordinarily ludicrous errors perpetuated by people who only fact check things against other Internet sources that are in turn repeating the things they saw on the Internet in a colossal daisy chain of misinformation, so there's every possibility that this is nothing more than a scurrilous slander to the people of Alabama. But it certainly does illuminate a bizarre psychosocial trend--people who celebrate the Confederacy, fly the Confederate flag, wear clothing adorned with Confederate iconography, and yet claim...with all apparent sincerity in some cases...that this is not a racist act and they are not racists. They are simply, as most say, "displaying Southern pride".

So this question is aimed to those people. Specifically, assuming we actually can set aside the inherent racism in the establishment of the Confederacy (and I want to stress, this is actually ceding way more ground in the debate than I'm actually willing to do, because all the first-hand contemporary sources made it blatantly clear that the Confederacy was founded as an act of racism and an explicit endorsement of the right to own African-American human beings as property)...but setting aside the racism, what exactly are you "proud" of when you fly the Confederate flag to celebrate Southern pride?

Are you celebrating the treason? Because establishing the Confederacy was an act of treason against the United States government, and it certainly does seem like the same people who fly the Confederate flag as an act of "Southern pride" pair it with the American flag as an act of patriotism. Those don't seem particularly compatible.

Or is it the defeat? Because I mean, I hate to be the one to be the bearer of bad news here, but the South lost. The Confederacy was dissolved, the political aims of their movement (which again, let's not put too fine a point on it, was the continued legalization of a brutal and harsh system of slavery) failed, and their army was roundly and decisively defeated. This does not seem, to me, to be something to be proud of.

I guess I might just be a bit confused. To outsiders, the Confederate cause was one of racism, treason and failure. I keep hearing people say that the thing they're proud of isn't the racism. So is it the treason or the defeat that you're celebrating? Please let me know.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)